Salvador Dali’s melting clocks are perhaps the most iconic and enduring symbols of the Surrealist movement.

Salvador Dali’s Melting Clocks

Salvador Dali painted “The Persistence of Memory” in 1931, at a time when the world was experiencing significant political, economic, and cultural changes.

Culturally, the 1930s were a time of great artistic and intellectual innovation, with the emergence of movements like Surrealism in the arts and the rise of critical theory in the social sciences. In literature, the 1930s saw the publication of many important works, including George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” and “Nineteen Eighty-Four,” and the publication of the first volume of Marcel Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time.”

“The Persistence of Memory” is a Surrealist painting that reflects these cultural and political developments. Its unusual imagery, which includes melting clocks and other objects that appear to be in a state of flux, is meant to challenge traditional notions of time and memory and to evoke the unconscious mind.

The melting clocks are perhaps the most famous and iconic elements. These clocks are depicted as being made of soft, melting wax, with their hands bent and twisted as if they were made of putty. The clocks are shown lying on a landscape that is barren and rocky, with no vegetation or signs of life.

The melting clocks are meant to represent the concept of the “persistence of memory,” which is the idea that memories and experiences from the past continue to shape and influence the present. Dali’s use of melting clocks suggests that time is not fixed or absolute, but rather that it is subjective and can be distorted or altered by the human mind.

Dali’s “The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory” was painted in 1952, more than 20 years later. The painting depicts a landscape that is partially disintegrating, with objects melting and dissolving into the surrounding environment.

Dali Plans His Legacy

By the late 1970s, Salvador Dali’s health began to deteriorate. Still known for his flamboyant and eccentric personality, and he often made headlines with his unusual behavior and statements. In the last decade of his life, he made numerous appearances on television and in films, and he was often seen at high-profile events and parties.

In 1982, the death of his wife, Gala, would plunge his health into a sharp decline. He began to exhibit Parkinson-like symptoms, and battled with substance abuse. Salvador Dali did not have any children, but the thoughts of succession and death frequently preoccupied his mind. In 1983, Dali founded the Gala-Salvador Dali Foundation, which was designed to serve as the ultimate benefactor of his estate, and ensure that his legacy would not be tarnished by counterfeits following his death. At around the same time, Dali maintained a close relationship with his commercial partner, photographer, and friend Robert Descharnes. Descharnes served as the chairman of the company Demart, which produced and distributed prints, books, and other commercial merchandise in Dali’s name. Salvador Dali entrusted Descharnes with administrating the commercial rights of his intellectual property, inking a 20 year-long deal.

On January 23rd, 1989, Salvador Dali died of cardiac arrest. He was 84 years old.

The History of Dali Wristwatches

Later in 1989, Philippe Muller visits the New York Gallery of Modern Art, and sees Dali’s “The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory”, and becomes infatuated by Dali’s surrealist depictions of melting clocks. Muller at the time was the director of Exaequo, a Geneva-based watch manufacturer.

One can only assume whether Muller’s intentions stemmed from purely commercial interests or not, but it was the inception of his idea to place Dali’s legacy onto the wrists of his admirers. Philippe Muller approached Robert Descharnes with the idea and his ability to execute on his vision, and was subsequently granted the licensing support he desired. Exaequo Geneve would produce watches for Demart, to be sold in museums, galleries, and exhibitions as part of Dali’s rapidly growing merchandise portfolio.

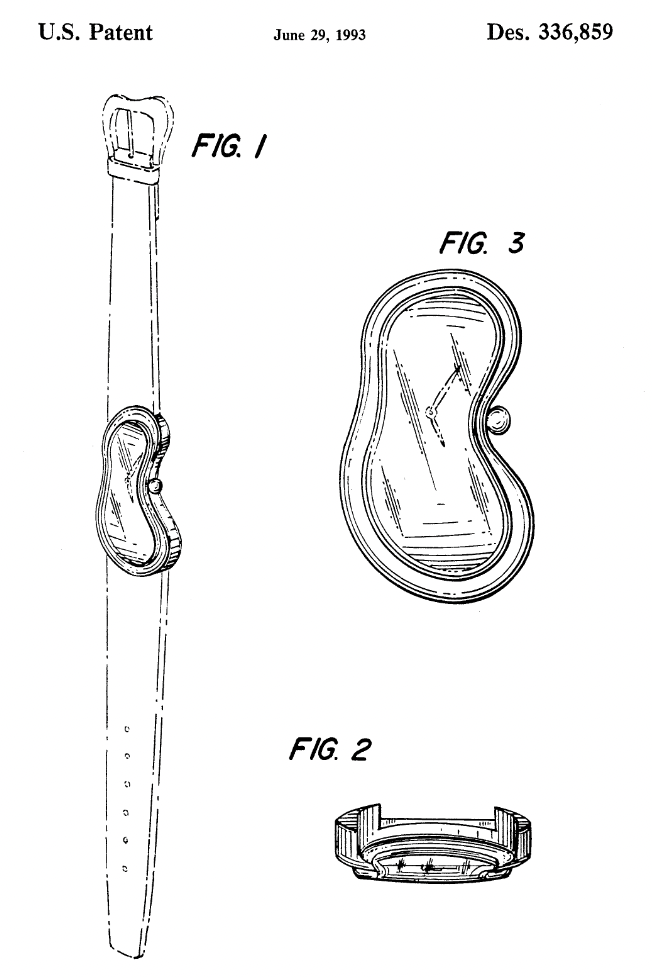

The watches would go on to trade under the Softwatch moniker. Philippe Muller filed, presumably, his first patent for the design of the Softwatch in 1991, evidenced by patent number USD336859S – granted in 1993.

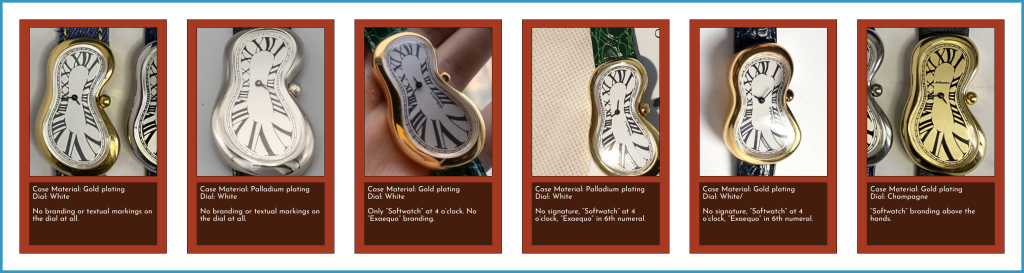

Earlier versions of this watch would appear with the dial missing Dali’s signature, simply carrying the name “Softwatch”

Later versions of this model would sport images of Dali’s various works, and feature his iconic trademark signature.

The model was offered in a steel or electroplated-gold case, with a variety of dial and strap combinations. All watches featured the same generic, Japanese, quartz movement at the time. Watch enthusiasts may wonder why a Genevan watch brand would employ a battery-powered movement over a traditional, mechanical movement. It is likely that a mechanical movement would have been too difficult and costly to execute at scale. By the late 1980s, the quartz crisis forced many traditional Swiss watchmakers into bankruptcy. Quartz movements notably featured a smaller form factor, which made them commonplace in ladies’ models.

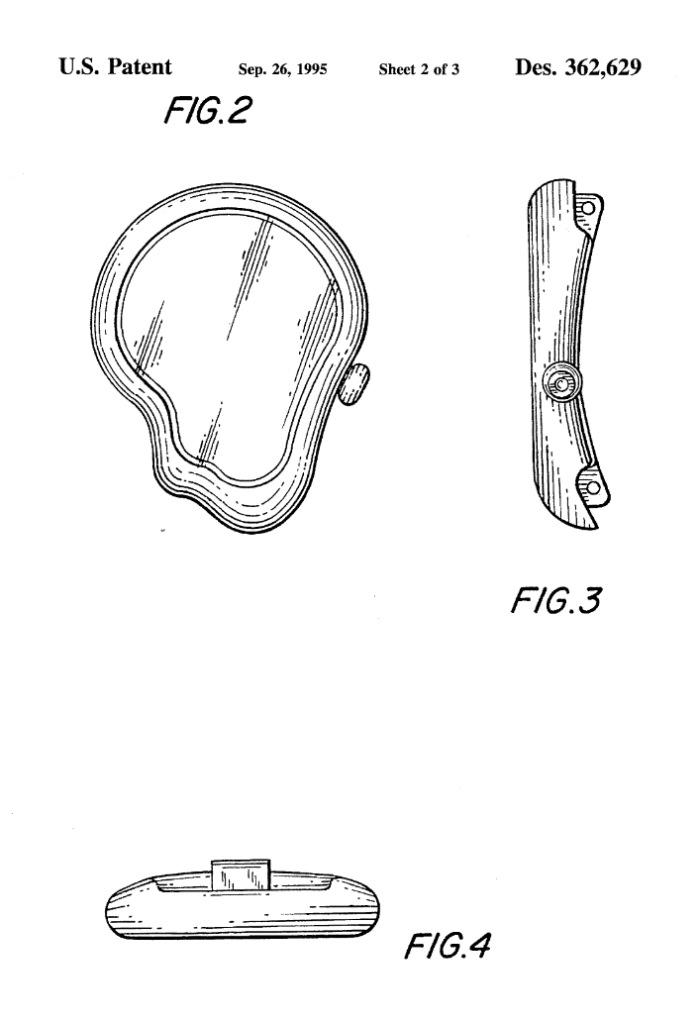

Philippe Muller’s first Softwatch was a success, and in 1994 he applied for another patent (USD362629S), which was quickly granted by 1995.

The watch would be available in fewer dial combinations, but also in steel and gold case finishes.

There was no other patent filed by Demart, Exaequo, or Philipp Muller for watch cases since.

The Lawsuit Era of Dali’s Watches

Entrusted with Dali’s intellectual rights, Robert Deschanes remained quite liberal in allotting licensing for more merchandise.

Exaequo Softwatch Models

Several trends can be attributed to the rise in popularity of the Exaequo “Softwatch” model. First, the undeniable increased popularity of vintage and neo-vintage wristwatches. Information pertaining to smaller, since defunct, watch brands is becoming readily available through community efforts across collector and watch enthusiast forums. Ultimately, it makes it easier to discover a niche brands that cater to the style and taste of individual collectors. Similarly, the Cartier Crash, adorned by celebrities and collectors alike, has prompted many to seek out similarly asymmetric watch case shapes.

Nevertheless, the full picture of the Exaequo Softwatch remains unclear. Due to the troubled late history of the brand, it is questionable when exactly Demart stopped selling the models. It will take the joint effort of collectors of the watch brand to fill in the missing pieces.

One such effort is undertaken by Ivan Struk at Strukwerk.com, who first encountered the watch brand in an attempt to source an asymmetric watch case similar to that of the Crash.

The following list represents an unofficial breakdown of all variations of Exaequo’s Softwatch.

Prototype I Series

These models are characterised by the total absence of the trademarked “Dali” branding. Anecdotally, the most collectible variant is the gold of palladium plated watch with no Exaequo or Softwatch branding. The watches came with a variety of patent leather bands, mostly in green and black. These watches, like all Exaequo models, featured quartz movements of presumably Swiss origin. Some collectors report these watches first made their appearance as early as April 1989, at BASEL, which is unlikely due to the short turnaround time that would have been required following Dali’s death, Philippe Muller’s inception of the Softwatch idea.

Prototype II Series

This series sees the introduction of champagne and bronze dials, as well as the first uses of rose gold electroplating and Arabic numerals. Interestingly enough, champagne and bronze dials would not go into regular production. They were never identified with the trademark Dali logo. Exaequo would not employ Arabic numerals until the third case design.

Series I

By many accounts, these watches define the first real production run. Available in yellow gold or palladium plating, with white or ivory dials. These watches sported the busiest dials in the history of the brand. For the first time, the Softwatch featured the trademarked Dali logo, and a “Swiss Made” label at the 6 o’clock position. The watches came in a variety of strap options, all leather. It remains difficult to find these watches in the second-hand market in NOS conditions with complete papers. Some collectors dislike this series, preferring the prototypes for their cleaner look.

Series I Deluxe Series

What distinguishes the Deluxe models from the normal Series I is the lack of Exaequo’s branding, which was moved to the back of the case. Available in several dial colours and strap combinations, these have become extremely collectable. Many collectors regard the red as one of the rarest of all Softwatch models.

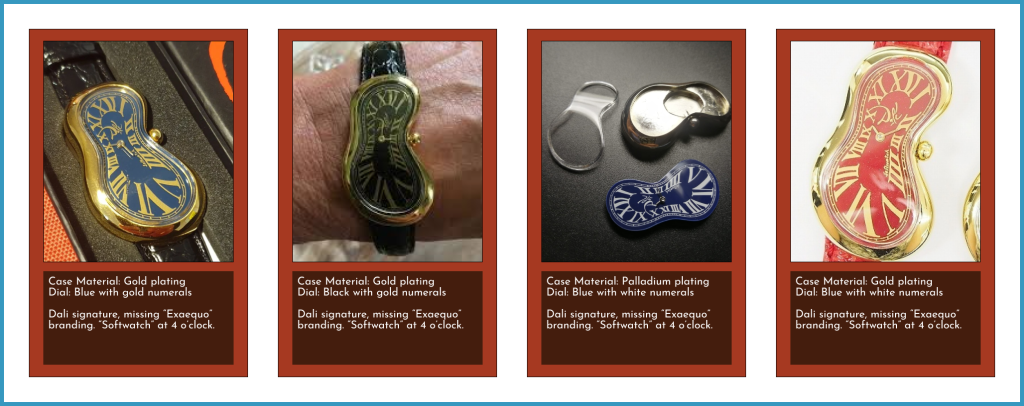

Series I Museum

The Museum Series was a bold move for the Exaequo brand and Demart. It is suspected that the first series served as a proof-of-concept before redesigning the case shape later. Available only in yellow gold plating, the dials of these watches featured notable Dali artworks. The dials were also decorated with gold pin markers.

Series II Museum

A notable change is recorded with the second series of the Museum collection, a new case design. Collectors often describe this form factor as the “gut” case, and the prior model as the “skinny” case. The gut case is characterised by a distinctly thicker top and bottom. A lot more art dials are available in this case shape, including some of Salvador Dali’s most popular works, including “The Elephants”. There is also an edition that features a portrait of Slavador Dali himself, which is regarded is the more collectable variant.

Series II Diamond

These watches were marketed as collection items, and were available in palladium and yellow gold plating options. For the first time, the dials of these watches were adorned in cubic zirconium (real diamonds, by some accounts) dial markers. Presumably, this is Exaequo’s first take on a limited run watch. Very few examples of this model have surfaced in classified ads.

Series II

This series, disregarding Museum and Diamond editions, is perhaps Exaequo’s most random. Exaequo brings back Arabic numerals, and introduces a black dial options for the first time. The gut case necessitates a smaller dial, making the dials look busier. The black dials fill the empty space with a “Swiss Made” label. Nevertheless, the red and blue dial variants, with gold printed numerals, appear more balanced – making them more desirable.

Series III

Exaequo introduces a new case shape, derivative of the clocks depicted in Salvador Dali’s “The Persistence of Time”. With the new case shape comes an offset crown, and new Breguet-style hands. These models were available in Roman and Arabic numerals, gold and palladium plated cases, and several dial colours. The champagne coloured dial makes a resurgence in this series. Evidenced by patent filings, these watches would be sold during the mid 90s.

Series III Deluxe

The Deluxe version of the Series III features a redesign of the numerals, with the “Softwatch” branding moving between the 4th and 5th position. Most importantly, these dials featured embossed lettering for the first time. Few models are documented.

Series III Diamond

Similarly to the Series II, this iteration comes from the “Collection Item” collection. The dials feature diamond or zirconium markers, which appear to be smaller than on the Series II.

Series IV

The rarest series of the Softwatch. These are very poorly documented, and appear to have been sold throughout the early 2000s. It is the only case shape with no corresponding patent documentation. It is also possible that this was a model that was short-lived due to lack of popularity. Strangely, these dials only came in Arabic numeral configurations. Although only gold-plated variants are pictured, palladium plated cases have made appearances on eBay ads from Spain. Unlike previous models, these were sold in box packaging. Furthermore, the “Softwatch” branding does not appear anywhere on the dial or case back, and the trademarked “Dali” branding is replaced by the artists full name.